There are estimated to be at least 1,000 cults operating in the UK. Here, a former cult member shares her story, and shines a light on the horrifying psychology of cults around the world

I became involved in a supposedly “left-wing” political cult known somewhat mysteriously as “The O.” (short for “The Organization”) back when I was a young woman of 26, living in San Francisco in the Eighties. I learned about The O. through two good friends, one of whom had been a member. It was, he told me, a progressive group focusing on issues I was passionate about: women in the workplace, women’s healthcare (a big problem for poor people in the US), affordable childcare, and union organising, among other things. Although I was an independent, feisty and feminist woman at the time, I nonetheless got sucked into this group that ended up controlling the most personal aspects of my life for the next decade.

My entry into the group was slow - it took about two years, at which point I moved to its headquarters in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Soon after my move I was encouraged (or looking back, ordered) to marry a fellow member, and then, rather quickly, to have children. By this time I was totally immersed in the world of The O. This meant cutting off outsiders, keeping my involvement secret from them (for “security” reasons), working up to 18 hours a day, and sleeping for only four to five hours a night.

I became cemented into a world that, it turned out, did none of the things for which I had originally signed up. We ran a couple of small businesses, but seemed mostly to be turned in on ourselves. When I questioned this I was told to “struggle with the practice and it will become clear”. I also learned that asking questions reflected my “bourgeois” side and was really not to be done. Once I had a husband and family within the group, and had cut off all my other ties, it became increasingly difficult to trust my own feelings or to find a way out.

Members of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, an alleged cult, arriving in court in 2008

After 10 years, while fearing for my young children’s wellbeing, I finally managed to drag myself out of the group with the help of two other disgruntled members. Unbeknown to us, the leader of The O. had been imprisoned for manslaughter for a year, so there was a let-up in the exhausting, mind-numbing schedule. In this breathing space these two other members slowly began confiding their doubts with me – even though it was hard to establish trust between us, for fear that we would turn each other in to “leadership”. At this point I could not even share my doubts about the group with my husband.

With great trepidation we began to plan our way out, and three months later we left together. As I began the long road to recovery and tried to clear my head, I was left with this question – how on earth could this have happened to me?

I first wrote a memoir – Inside Out – about this experience, and then I set out to study this question in depth ending up with a Ph.D. in social psychology and recently, a second book: Terror, Love and Brainwashing. The popularity of shows such as Netflix’s Wild Wild Country prove that cults are still of huge interest.

Now, 27 years after I left The O., cults continue to entrap, abuse, and sometimes kill people around the world. Although both women and men experience cultic abuse, women remain some of the victims most harmed by cultic control and exploitation. Below I detail more of my experiences, and explore the psychological impact of living in a cult.

The most infamous cults

Perhaps the most infamous cult of modern times was Reverend Jim Jones’ Peoples Temple. In 1978 over 900 people, including many women and over 300 children, lost their lives in the Guyanese jungle. A suicidal Jones forced them to drink poison-laced flavour-aid (this tragedy has entered the language as “drinking the kool-aid”) so that he could take his followers with him as he died. These followers did not do so voluntarily, as was popularly believed at the time. Rather, they were surrounded by armed guards, deep in the jungle with no transport out and no passports, weakened by Jones’ physical and psychological abuse.

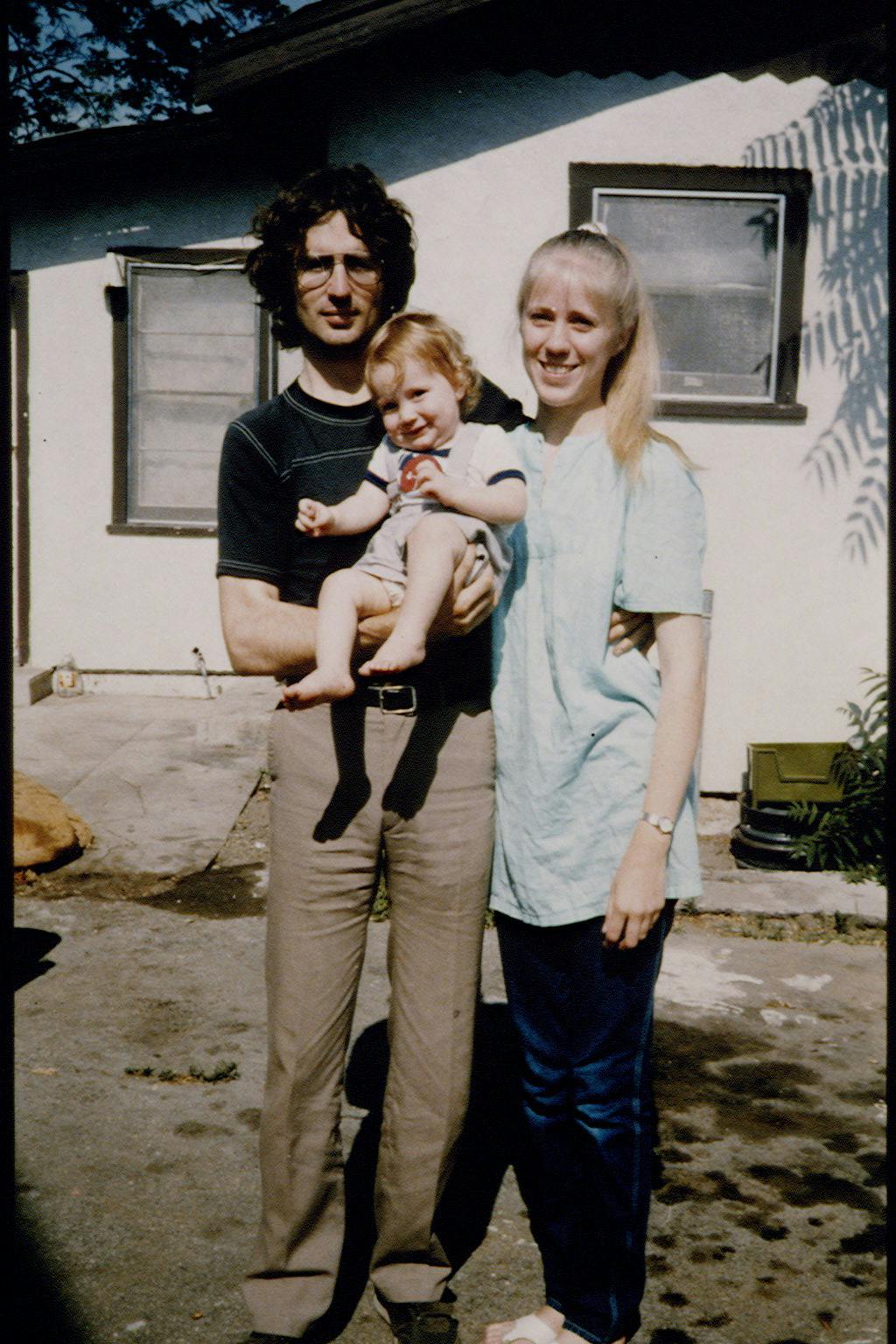

A portrait of Jim Jones and his family. Jones led the mass murder-suicide of over 900 people

In Waco, Texas, in 1993, a fire started during a 51-day standoff between the Branch Davidian cult and the FBI killed at least 75 followers of the fringe preacher David Koresh, including about 25 children who he had held hostage in his compound and allegedly sexually and physically abused. Koresh had claimed the women in the group and some of the girls as young as 10 as his “wives”.

In the year 2000, nearly 1,000 members of Joseph Kibwetere’s Ugandan cult, The Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments, died – many in a fire in a purposely-locked church, and others through poisoning and other means. Most of these victims were women and children. The motives are unknown, although it has been proven to have been a purposeful mass murder.

These particularly murderous cults are merely the tip of a very large iceberg. But beyond these groups exists a vast array of other highly controlling groups which, although they may not engage in murder, do share many of the same attributes of extreme control of people’s lives and an assortment of abusive behaviours and exploitation. While my time in The O. was not defined by murder, the group controlled every aspect of my life for the decade that I was a member. I was chronically sleep deprived, told who to live with, and even who I could marry.

Ian Haworth of the Cult Information Centre estimates that at least 1,000 cults are operating here in the UK. Numbers are hard to come by, however, as many, like The O., remain secret. The UK also currently lacks a legal definition of such groups.

Cult leader David Koresh with one of his wives and their child. Koresh claimed girls as young as 10 to be his “wives”

Now I receive enquiries from women concerned about cults in the UK on a weekly basis. They are either former members trying to get help, or women with friends or family who are at risk of joining cults, or are already in cults. The cults in question include organisations based on a variety of religions but also so-called wellness programmes, such as yoga, as well as personal growth, educational, political, therapy, philosophy, sales or workplace-based groups. A South Korean cult – Jesus Morning Star/Providence – has even been accused of allegedly recruiting young women off the streets, promising (but not delivering) modelling careers.

How do cults operate?

A wannabe cult leader can use anything they think will work in a given time and place as a means to draw people in, isolate them and begin the process of gaining control of their lives.

Cults are started and led by charismatic and authoritarian leaders, just like the leader of The O. These leaders share traits with psychopaths: a combination of being charming with a grandiose sense of self and an incapacity for love, along with being cruel, having a lack of empathy, remorse or guilt, and being skilled at manipulation and lying. Although most cult leaders are men, cultic abuse has been alleged to occur in many women-led groups such as Siddha Yoga, Sahaja Yoga or the Australian group The Family.

The NXIVM cult currently making headlines due to the horrific branding of women members is led by Keith Raniere, but his top-ranking lieutenants are women, all recently arrested and charged with sex-trafficking, extortion and other crimes. Allison Mack, a former child actress and star of Smallville, was one of these co-leaders, while also being one of Raniere’s “slaves”. She has been accused of recruiting other women as sex slaves and has been indicted on charges of sex slavery and forced labour conspiracy.

Allison Mack has been accused of recruiting women as sex slaves for the NXIVM cult

Cult leaders (or sometimes leadership groups) rule over closed group structures that are emotionally, socially and psychologically isolating. They do not, however, have to be geographically isolating. In my group, we lived together in flat shares in the Minneapolis and also had jobs in the outside world. But our interactions with outsiders were strictly limited. People in cults are often taught that they are the elite (although only the leader is perfect), and that those outside of the cult are lacking at best, and evil at worst. Within the cult one is taught not to speak freely to other members – communication has to be strictly within the cultic language and boundaries, which was the case in The O. Doubts must certainly not be shared and eventually, followers learn to repress their own critical thoughts.

The leader controls the belief system. No other beliefs are needed, or allowed. One belief, one “truth” fits all. When I became a member of The O., I thought I was joining a Marxist-Leninist political organisation that aligned with my own beliefs. It soon became apparent, however, that this was not the case – the leader seemed more focused on running the group’s small businesses than anything political. He communicated with us mainly through memos, and frequently used the acronym P.O.O – although none of us were allowed to know what this meant.

Similarly, in NXIVM, all knowledge came from Raniere – supposedly a genius – and inner circle followers allegedly had to recite his 12 Commandments daily. Commandment 11 states that followers “pledge to ethically control as much of the money, wealth, and resources of the world as possible”, since “it is essential for the survival of humankind for these things to be controlled by successful, ethical people”. And commandment 12 (tragic irony alert) states that a world made up of Raniere’s followers will “be a better world …. (where) People will no longer try to destroy each other… or rejoice at another’s demise”.

Processes of coercive control or brainwashing operate within cults. Once a person is isolated from any differing points of view, it becomes very difficult to stand up and object. During my decade in The O. I was isolated from most of the other members of the group, which was one of the cult’s ‘security’ measures. In a cult, even if one knows all the other members, one can’t share doubts – this is the biggest “crime” and people sharing doubts will be criticised or punished. This keeps cult members from talking about and understanding the control mechanisms and reality of the group.

But more than that, cults engulf followers within their own world almost entirely, and then claim it, and the leader, are the only source of goodness and truth, and the only ones who care about you. But at the same time, the cult creates stress and feelings of threat through constant, alarming messages about oncoming disasters and what will happen if followers are not loyal enough. A cult might also humiliate followers, and make them feel guilty and ashamed for not doing enough. Rewards and punishments are wielded to remind followers just who has the power. I later learned from other members of The O., that boxing matches were set up to pit members against each other and “heighten struggle”. The paranoid nature of the group was also evident in the fact that our meetings were often held with the radio blaring in the background, in case anyone from the outside was attempting to listen in.

Human beings have evolved to seek comfort from a trusted other when anxious or stressed. Cult leaders abuse this normally healthy instinct by setting themselves up as the only supposed trusted other – even as they are creating the stress. This method of alternating “terror” with “love” can result in a trauma bond where the follower becomes too afraid to do anything but cling to the group. Without being able to fight or flee from the group-created threat, followers freeze in both their thoughts and their feelings about the group. They become unable to think about their own feelings and their own experience, meaning the group can begin to do their thinking for them. Followers can end up becoming totally dominated by the cult, and unable to protect themselves or their children.

In the O., I had to work incredibly long hours in the group’s various organisations, which included a wholemeal bakery. This left time for only four to five hours of sleep every night, meaning I was so exhausted I barely had time to realise how deeply the group dominated my life.

This is a psychological process that has been illegal in the UK since 2015 – but only if it occurs within an intimate or family relationship. It’s called coercive control and it operates in many situations of domestic abuse. Like the controlling boyfriend who starts out charming and full of loving gestures, but ends up isolating and threatening his victim, controlling her communications with others, her movements, her money and her very sense of self, cult leaders use these exact same methods to control their followers. Yet no law exists in the UK to protect us from these psychologically abusive methods within groups.

Warren Jeffs, the leader of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, was charged with two counts of rape as an accomplice in 2007

How do cults recruit members?

People often think that it is weak, needy individuals who “join” cults. But no-one joins a cult – people join groups they think will be positive in some way. In my case, it was to help fight for social justice, and when I initially joined The O. I was assessed on my “ideological form”. As a feminist, I was stunned to be told that I had the ideological form of a “male chauvinist”, but at that point I was already so confused that I reluctantly accepted this absurd label.

For other women, unintentional entry into a cult may be to do yoga, to develop their professional network, to improve their health, or any number of other reasons. Often it is intelligent, productive and perhaps somewhat idealistic people who are recruited.

A person’s vulnerability to cult recruitment is more likely to be a situational one: for example, if they’ve gone through some kind of transition that means they may be open to new friendships, networks or experiences. Have you recently moved? Started or just left university? Broken up with a partner? Changed jobs? Experienced a bereavement? These kinds of normal life transitions can be a time when an approach from a group may appeal. If you’re lucky that will be a healthy group. If not, and you don’t know the warning signs of cults, you may find yourself targeted by a dangerous cult initially appearing as a benevolent group offering something attractive or interesting. The women in NXIVM thought they were gaining influence, a “sisterhood” and self-fulfillment “by eliminating psychological and emotional barriers”. They didn’t imagine this would end in sexual abuse and the painful, humiliating branding of their bodies.

A sign at the Albany headquarters of NXIVM offers “executive success programs” - with no mention of the horror within

There are many recruitment techniques that cults use in the early stages (much like that abusive boyfriend scenario), such as love-bombing, promising the world, flattery and so on. But it is the control of other close relationships within socially isolated environments that is the key to how cults maintain their grip, once the initial recruitment has taken place. We can predict that cults will have high rates of sexual and physical abuse given this need to interfere with normal family life, as well as the lack of exposure to any oversight from outside authorities or concerned others who could intervene.

For women, the entry points into cults are not that different than for men. But what happens to women in cults can differ. Many religious cults put women in extremely subservient roles – such as the polygamous Fundamentalist Church of Latter Day Saints, where an elderly man may have up to 60 wives including underage girls. Women may be put into arranged marriages or relationships quite quickly, while hardly knowing their future spouse, as happens with the mass weddings of the Unification Church. This, of course, helps trap a woman into the group. Other cults insist on celibacy, such as in the late Sri Chinmoy’s fitness and spirituality cult. He allegedly forbade sex even for most of those he had arranged marriages for – except for sex with himself that he coerced from inner circle women, some of whom were born into the cult and knew little of social norms outside. Yet others have been alleged to enforce polygamy and sexual abuse of children as in the Children Of God cult, which both Rose McGowan and Joaquin Phoenix were born into.

4,000 couples gather to take part in a mass wedding organised by the Unification Church in September 2017

Bikram Choudhury of the popular hot Bikram Yoga empire is now on the run from an arrest warrant following a court judgement against him, as well as numerous sexual assault and rape accusations. The #MeToo movement has encouraged some women to come forward with allegations of sexual assault and misconduct against Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche of the Shambala Buddhist community. These abuses have occurred as the result of the likely cultic nature of these organisations, which encourage followers to leave critical thinking at the door.

Along with sexual abuse, cults usually control if and when female followers can have children, sometimes as a way to punish or reward them. Some may even dictate abortions, as former members of Scientology have alleged. Heaven’s Gate allegedly forbade followers from having children, and those who already had children were encouraged to abandon them. Other cults forbid contraception and women may become “breeders” for the next generation of loyal followers.

If there are children, this relationship is likely to be closely managed by the cult. Often children and parents are separated for long periods of time. After I left The O., the leader attempted to separate me from my two children by ordering my husband, who had not yet left, to try to gain full custody – luckily, The O. was not successful in this attempt.

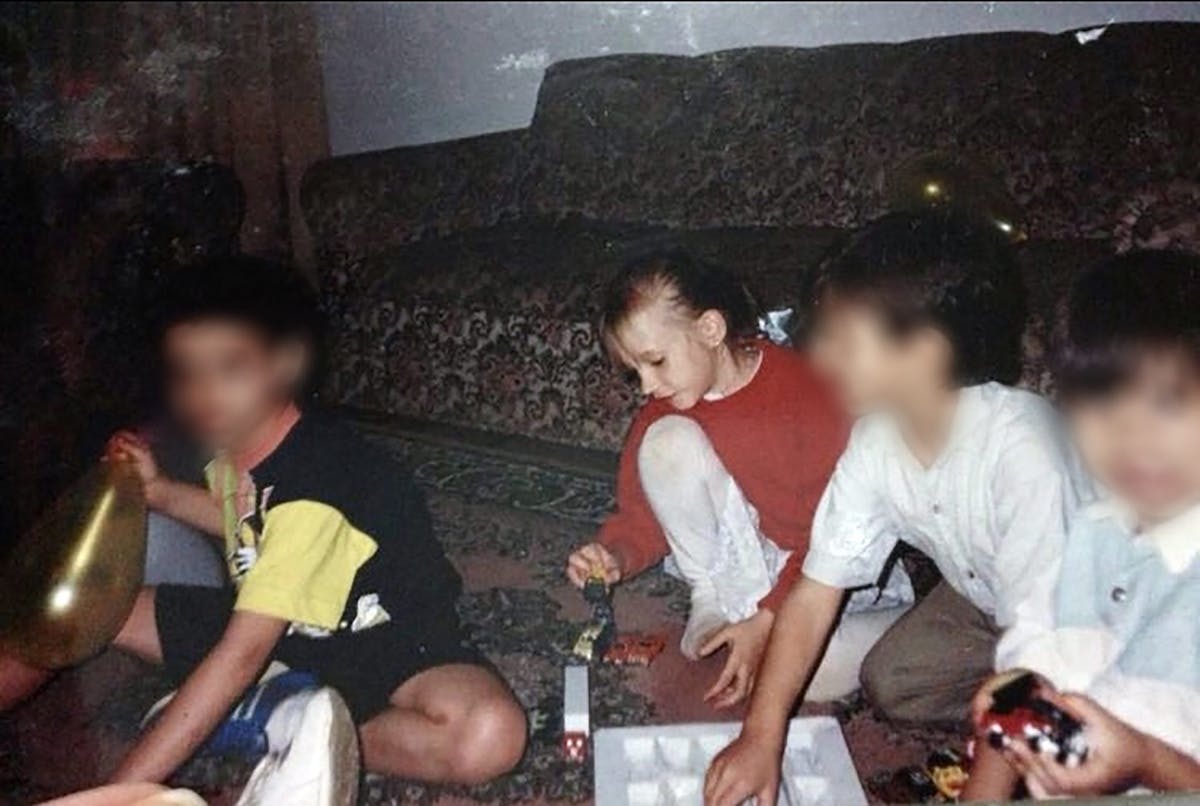

In Koresh’s Waco compound, however, the concept of family didn’t exist and children often barely knew who their mothers were. In other groups, mothers are kept so busy that they have little time to spend with their children, or that time may be taken up with cult duties, meaning mothers are unable to give their children appropriate attention. Parents can be forced to brutally “discipline” their children. In the Twelve Tribes group - supposedly the “Sons of God” – young children are allegedly beaten with rods and forced to engage in many hours of child labour doing farmwork, in order to supply the hippy-ish cafes they run. From the outside, this group may seem benign and quaint, but there are now many former members speaking out with allegations. One mother said: “There wasn’t a day that went by while I was there that children weren’t beaten with the rod. I beat my own son because that is what the group taught me to do.”

Numerous cases of alleged child sexual abuse within the Jehovah’s Witnesses are currently being investigated. The Governing Body had allegedly covered these up using their two-witness rule – a rule that states abuse can’t be taken seriously unless two people witnessed it, which is obviously designed to prevent exposure of these crimes. In these types of cases, mothers are unlikely to be able to protect their children when trapped within the stifling and punitive cult system.

It can be exceptionally difficult for young women (and men) who grew up in cults to find a way to leave: their families may shun them or at least greatly limit contact. They may often have very little understanding of how to operate in the outside world, and there are very few resources to support them. The practical and psychological barriers to building a life outside can be overwhelming. When I finally left The O., I learned to embrace my new freedom. It was spring at the time and I felt ready for a fresh start; I was returned to the land of the living at last.

And there are many other strong and resilient women who have done as I did, and who are now leading efforts to expose the alleged abuses within these closed groups. These include survivors of the Children of God cult, of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, of the Twelve Tribes, and many other groups. The US TV star Leah Remini spent much of her childhood in Scientology but, having left, she has gone on to make an award-winning series about the true nature of life inside.

Dawn Watson, who escaped from the Children of God cult when she was a teenager

If cults didn’t tightly control followers’ close relationships, then these followers would be able to share doubts, and have true safe spaces in which to critique the group and to resist. If cults were more open, followers would have access to other information, beliefs, and criticisms of the group. The psychological control of the trauma bond would then fail.

That’s exactly what happened in my case: in addition to a growing concern for my children, having two others in the cult with whom to share doubts and fears about the group allowed us to begin thinking critically again. Almost as soon as we did this, we were able to plan our way out. For others, having just one confidante can be enough to break the chains.

So when embarking on a new involvement, it pays to do a bit of research – find out if there have been complaints or critiques about any group that exhibits cult warning signs, or that seems too good to be true. Watch out for anyone who suggests you drop your friends and family for a greater good, who tries to totally engulf you within a new environment and set of beliefs, who claims they are the only safe place, and who puts you under constant stress “for your own good”. These are signs of a potentially highly controlling situation. And knowing these warning signs could save you a whole lot of grief and heartache.

Source: The Stylist